The COVID-19 virus is truly devastating. And yet, there are challenges out there that can make this one seem less significant. For one, I'm thinking of Alex Lewis from England. I featured in my newest book, "Pushing The Boundaries! How To Make Life Awesomer" which I'm currently seeking a publisher for). If you're feeling down coping with the pandemic, have a look at Alex's story: I hope it will inspire you and help float your boat: Chapter 12 ALEX LEWIS I've been asked, "Who's your favorite interviewee in the book?"

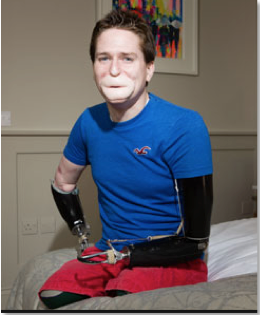

Now, that's a little like asking a parent to name their favorite child. The question might be better asked if one person stood out in terms of impressing me. Equally hard to answer, but pushed into a corner, I'd surely have to name Alex Lewis as one of the top contenders. The following chapter is unlike any other in this book. So sit back and watch what happens. You see, the man you're about to meet, Alex Lewis, has pushed boundaries beyond what I would have thought was possible. No, he hasn't crossed gorges on a tightrope or wheelchaired himself around the world or anything like that. And yet, what Alex has accomplished is about to blow your mind. Talk about courage! OK, I've mentioned previously that people are always asking where my ideas come from on whom to include in my books. Well, in this case, it was a newspaper headline that screamed out to me: "Quadruple amputee calls year of illness brilliant." Huh? "Brilliant" being used to describe the illness of an amputee? I look further. Overleaf, I discover a photo of a man sitting in a wheelchair. It is apparent he has no legs. No arms. Clearly, surgery has been executed on his face. The sub-head calls out: "After losing his legs and arms to devastating infection, his life changed from lazy to dedicated." From lazy to dedicated? Now, you tell me: how could this man not be a candidate for an example of someone who’s pushing the boundaries? “You’ve referred to yourself as a ‘regular bloke’, Alex,” I say to the Englishman as we settle in for our discussion. “But I have to tell you, I don't see you that way.” He laughs, a real chuckle, not a patronizing chortle for the interviewer. “Well, I still see myself that way, Peter. Honestly, I feel that way on a regular basis," he says. “Really? OK, but as a guy who pushes the boundaries across so many levels…” “I still think I’ve got a long way to go,” he jumps in. “I think I could do a lot more. In my state, this is just the beginning. I want to keep moving forward, keep helping other amputees… I mean, this may sound ridiculous, but I’m kind of glad all of this happened to me.” And just what is “all of this”? Very simply, it’s the extraordinary story of Alex Lewis enjoying pints of Guinness one evening with his mates at The Greyhound, the local pub in Stockbridge, Hampshire, England he co-owns with his partner Lucy. But the handsome, six foot, laid back guy begins to feel his throat getting scratchy. "I thought I was coming down with the flu," he tells me. “But that flu went away, leaving in its place a disease not nearly as forgiving.” Days later, Alex is in a fight for his life. He's fallen victim to a mysterious bacterium that begins turning his skin purple and tearing away at his flesh. He will learn later that this normally harmless bacteria is usually filtered out by the body. But in his extraordinarily rare case, it’s developed into septicemia and toxic shock syndrome. His major organs shut down. Alex spent a week in a coma as the deadly bacteria wreaked havoc through his body. His feet, fingertips, arms, lips, nose and part of his ears turned black. And then the worst happened: doctors were forced to amputate both his legs above the knee and his left arm. If they didn’t carry out these extreme amputations, the disease would kill him. He also lost part of his nose and lips. And in a pioneering 16-hour operation, the medics attempted to reconstruct his remaining arm in a bid to save it. The odds were poor: Alex was given a three per cent chance of survival. But the medical team was unaware of who they were up against. This former knockabout – a guy who admits to having been unmotivated, didn't work hard, drank a lot (he was the landlord of the pub, after all) and spent more time socializing than actually working – found he had untested willpower beneath the surface that until then had never seen the light of day. He fought back. Still, the fates were not finished with Alex Lewis. His right arm broke when he rolled over in his sleep: the Strep has worked its way inside the bone. It now had a clear path to his torso. There was little choice for the doctors but to remove this one remaining limb. “And that meant for me the beginning of a new, utterly unknown life as a quadruple amputee,” he tells me. The future held countless more gruelling operations to rebuild his face. The daily program also included lessons on how to walk again with prosthetics. But the worst, devastating moment for Alex occurred when his three year old son looked at him for the first time post-operations and recoiled in horror. “Sam struggled to come to terms with my drastically altered appearance,” he says, “and I can’t blame him one bit. I mean, my face was completely unrecognizable, I’ve got no legs, no arms… for a little boy to look at that, having seen his father upright, normal...” So shocked was the child that he could no longer bring himself to kiss his father's disfigured face. (As a dad myself, this is a situation I can't imagine.) The pair struggled to bond anew. “Peter, it was an awful period,” Alex confesses. “I was a stay-at-home father for more than two years before I fell ill. It was fantastic. Sam and I had a very close bond. Then all of a sudden you’re thrust into something you have no control over…” Alex tells me he really shouldn't be here, should not have survived. “There are 10,000 people a year who contract Strep in some form, and of those about 9,600 die. Of the remaining 400, only about 10 have quadruple amputations. “I’m one of the lucky ones, definitely,” he concludes. Let me ask you this, faithful reader: had you lost all four of your limbs... had you also had most of your face taken away due to a rare infection... would you consider yourself lucky? Kinda puts things in perspective, doesn't it? After leaving the hospital, Alex had very little information. “You don’t know what’s going on,” he explains. "So what I want to do long term is to bridge that gap and create information so people can understand more, set benchmarks, etc. You know, when you’re facing this kind of traumatic situation, you need to know what to do, who to talk to. Right now, you have to go searching for it, but I think that shouldn’t have to be the case. I mean here in England, there is help available but the problem is, it’s not easy to find. You have to go hunting for it. You know, you've gone through something that's terrible, but it’s not just you: it’s your family members, it's your friends, your children… there are a lot of people involved. I was very lucky that my family and friends were so strong and active and they got me through all of it. My little boy is so wonderful. Sam's kind of the glue really that's kept us all together, in his own way. That, and I had a great family unit around me… but a lot of people don't have that.” “So, as I understand it,” I say to Alex, “ at this point in your life, you really do feel very fortunate.” “Peter, I am fortunate, no doubt about it,” he insists. "Do you feel courageous?" "Hmmm... courageous... not so sure..." I suggest we explore this a bit more since I expect there are people who, if they ever experience what Alex Lewis has been through, might not call upon themselves to go out and help others. So I ask him what lies behind his desire to be of assistance to others. “I think, very early on, I didn’t realize I wasn't dealing with it that well,” he says. “I just took every day as it came. Whether it was losing my left arm or when I broke my right arm. But you know, I think when that right arm had to be amputated, that was the point where I could actually cope with it. I could deal with things and I could see myself moving forward after the surgery. I had an idea of what I wanted to achieve. I think it was at that point that I just knew I could go out and be able to help other people. You know, work with universities, colleges, schools... doctors, surgeons, the National Health Service… and talk about what I've been through and the amazing care that I had.” Alex tells me he had a great stay while in hospital. "I look back on that time and it was one fit of laughter. It sure wasn’t a bad place. My family and friends... our senses of humor had to remain intact. So I feel I've been very fortunate.” And there it is again: what a lesson to learn in bravery. To feel fortunate after what Alex has endured is really quite incredible. Back in 2014 when Alex returned home from the hospital, he was insistent that Lucy continue her job running the pub and guest house near Stockbridge rather than become his care giver. That was crucial, he thinks, to maintaining a semblance of normality. “It’s very tempting to give everything up for a partner, but I didn’t want Lucy to become a live-in nurse, seeing me as her patient and having to take care of me,” he says. “I wanted her to continue to have a life.” For her part, Lucy says, “If you love someone, I think you just deal with it. I said to Alex, ‘You’ve got a choice: either feel sorry for yourself and become a recluse and a hideaway – and you’ll lose your family if you do – or get on with it.’ You know, he had to feel like he was bringing something to the party.” “I'm very lucky that my partner is successful in her business,” Alex adds. “The mortgage is being paid by her, I can go out, and I can work. I'm free, I've got time, and I can work on the Trust... “Ah yes, the Alex Lewis Trust,” I say. “I'm keen to learn more about that.” Alex wastes no time filling me in on a movement he’s very proud of. “Early on, people got wind of what had happened and realized it was a common cold that became very nasty. And they got that my limbs were gone… and they learned how expensive prosthetics are, and that they’re unavailable on National Health, and what I would need in the long term… and that the cost of all this was quite frightening. (The estimate is £3 million – that’s almost four million USD – that he’ll require over the course of his lifetime.) People recognized we couldn’t afford this on our own: it’s hellishly expensive, and it’s a long, long road and it’s always going to be expensive, unfortunately. Well, that knowledge started filtering down and people started doing marathons and ultra-marathons, runs, walks, hikes, climbing mountains… whatever, to raise money for my future journey. And this gained some traction and a lot of people got behind it. They realized I had simply caught a cold that went awry. The got that this could happen to anybody, and there’s nothing you can do about it.” “Alex, when I think of the Trust and your commitment to helping other people,” I say, “it makes me wonder if you’re spiritual at all. What I mean is, do you have a sense that you were meant to go through this to help other people? Is there a destiny card at play here?” “Great question Peter,” he says. “Yes… I think perhaps… yes, I do sometimes think that. You know, at night, you lie there, quiet and think, yeah, maybe there is something behind it. I mean, certainly I was going down the wrong road before I got ill and I think it came at a good time. That’s why, in my mind, this has been a saviour. It very definitely altered my life for the better and got me to a place where I can help others.” “Alex, tell me about that ‘wrong road’ you were headed down." “Well, I mean, it wasn’t anything that bad, I just didn't work hard,” he confesses. “I drank a lot cause I was the landlord of the pub: I spent more time socializing than actually working. Looking back, I drank masses: I was easily an alcoholic. But you know what: I don’t miss those days. I just wasn’t doing enough, really, to help. I didn’t push myself. I’ve always been incredibly laid back, relaxed, which I’m thinking did help because with what I’ve gone through, patience is a virtue, and I’ve got lots of it. I mean, it takes a long time for me just to learn how to pick up a fork.” Alex stops for a moment, thinking about the huge amount of work he’s put into rehabilitation just to accomplish everyday tactics like grasping a piece of silverware, something most of us don’t even stop to think about. “Looking back, I wasn’t on the right path. I was such a big drinker before this happened but now, I hardly touch the stuff. Not something I need. So falling ill was a saving grace for me, and it’s got my head straight and clear. You make your choices as to what’s important… and I couldn’t go back to that way of life now. I’m very lucky: I’ve been given a second chance.” Considering my tactic of listening to my interviewees and then trying to drop myself into their lives to gauge how I'd handle things, I'm honestly not sure I'd be saying the words Alex is using about being lucky and being offered a new chance to move onwards. "But Peter, I’ve been forced to appreciate what I have," he clarifies. "This whole thing has allowed me to stop taking things for granted. Lucy, me and Sam: we've met the most amazing people, had the most amazing times and laughs, and the three of us are now so much closer together. It’s given me the kick-start I needed to get going again.” There’s a pause, and then he adds, “I know it sounds odd, but I owe this illness a lot.” And we’re still not quite done with this way of thinking. Displaying his amazing courage and engaging sense of humour, Alex tells me, “Ya know, a drunk in a wheelchair is not a good thing, not very clever, especially if you’ve got no arms. It’s one thing to fall out of a wheelchair when you have arms, but it’s another thing when you haven’t got arms and, you know, you just face plant. Not a good thing.” He laughs. And I try to. I should point out that there is a remarkable documentary by Leonardo Machado called “The Extraordinary Case of Alex Lewis”. You'll find it on You Tube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3kecUY47gw In many ways, it’s a love story. I'll warn you that parts of it are tough to watch, but by the end of the film, the mood is uplifting, full of hope, optimistic. Watch it, and if you don’t shed a tear, your heart’s made of stone. “You know, Alex,” I tell him, “as I looked at that documentary and heard you exclaim ‘Just Keep Going’, it reminded me of a lady I wrote about who was attacked brutally by a shark, Nicole Moore. As I described in my book Shark Assault: An Amazing Story of Survival, she lost her arm to amputation and almost her leg, and to this day deals with ongoing pain issues and more operations. Yet, she inspires everyone around her with her cheery attitude and desire to help others, just like you. Her mantra is ‘Keep Moving Forward’." “That’s amazing, Peter”, he says. “You survive something quite incredible and you have no reason to be sad. I’d rather be alive than dead. I mean, the thought of not being able to see my son again filled me with complete dread. But to come to it as I’ve done, I feel like I’m the luckiest man alive. And a large part of that is the ability to help others.” Wow. "I feel like I’m the luckiest man alive." Talk about resilience. And much as I'd like to think I'd have that spirit, I fear I wouldn't be saying the same thing if it were me in Alex's situation. I tell him that what’s surprising to me is that he and others like Nicole Moore and Rick Hansen are so motivated to help people who need encouragement. “Alex, I don't think of you as someone who’s laid back: indeed you seem to be very active and I’d describe you as someone who is indeed pushing the boundaries. Do you think that way at all?” “Well… I do like to think that I’m pushing some boundaries, yes” he says. “And I totally get why people don’t want to do the things that I’ve done. But sure, through the Trust, I donate my time three days a week. I travel, we work on projects with universities, talking about bionics and how the future can be shaped with prosthetics to help burn victims and to help amputees…” Alex stops momentarily to think. I sense the wheels turning as he considers his lot in this world. “I’ve got a small chance of making someone’s life a little bit better,” he says. “It’s a lovely position to be in.” He thinks back to coming out of the hospital after three months. A good friend visited him and stated point blank: “Nobody has affected me like you have with how you’ve handled what you’re going through. You’ve changed my life!” “To be able to have that affect on someone made me feel absolutely incredible,” Alex says. “I mean, you come away from that and say, My God, I can make a difference!” I tell this bold Englishman that I concur: his attitude is infectious. His resilience is – dare I say it – contagious. So, good natured reader, if you think you've got problems, let Alex Lewis be your motivator to put aside those issues and get on with it. Seriously. Your challenges and mine are worse than his? I doubt it. And then Alex shares another revelation: his best friend Chris gave up his role as a ski instructor in France to move back to Hampshire to look after him. “He actually gave up his job to come and live here! And he and I figured it out together. It was an amazing time: I could not have done it without him. He’s one in a million, that guy: just unbelievable!” With such a positive attitude at hand, I’m curious to know if Alex ever broke down during his stay in the hospital. You know, made time for a “pity party”. “Briefly, yes,” he tells me, somewhat uncomfortable with revealing the moment. “During the rehab phase particularly… it was so frustrating. But I just got my head around it and decided to figure it out. I couldn’t rest on my laurels. In my mind, I went through thousands and thousands of situations of how I would get myself out of that. Rehab – learning how to live with prosthetics – it was the only option I had. I needed to regain my dignity: when I went into the hospital, my dignity was left at the front door. I had to go home and regain it… and I was lucky there. I had to figure out these things in my mind, and so that's what I did. That kept me on the positive side.” “Alex, you had your mouth rebuilt last year in a pioneering 17-hour surgical procedure," I say. "As I understand it, the doctors took skin from your shoulder and remodelled it as lips. And the plan is for you to get more surgery to complete the job, which will include tattooing your skin to have it blend in with the rest of your face. All of that sounds pretty brutal to someone like me, a self-confessed avoider of anything medical. Are you up for this after everything else you’ve been through?” “You know what, Peter: I’ve had exceptional care from the medical team, so I trust them. I was in the best place in the U.K. for the kind of surgery I’ve had so far. I knew I had a great team working on me. Without those guys, it would have been a much different affair. So, yeah, I’m ready.” I've learned that in his motivational talks, Alex uses a somewhat humorous, light-hearted attitude. “What’s behind that?" I ask. "Ever feel you should be treating this in a deadly serious way?” “Look, there are times when I have to be serious,” he acknowledges. “If I was talking with a plastic surgeon, I was always serious then. And I was petrified there, to be quite honest; I think we all were. Of course, over the last three-and-a-half years, we’ve all become great friends. But I did take it seriously. Still, I also knew I had to have a light-hearted approach and that my sense of humour would be my back up. I needed that to get back to my comfort zone. I wanted to make it easy for the doctors too, so it wasn’t all doom and gloom. And I think that helped.” There’s a pregnant pause, a slightly cheeky look, and then, in a mock-serious tone: “After all, we’re British. A good sense of humor is quite key.” “Rule Britannia!!” I sing, which gets a guffaw. “But seriously Alex, does it surprise people when you do your motivational talks and display this humorous, light-hearted attitude? Are people taken aback by that?” “Yeah, they are," he says. "I think they expect me to crash and burn early on, and then pick myself up." Alex explains that people are amazed when he tells them he doesn't take all kinds of drugs to cope with things. All he wants to do is be a dad, be a good husband, be a father. "Then, if I can go out and aid people slightly, give someone a bit of a leg up, if you will, to see that in a dire situation there is hope… I think that’s what I’m trying to push more than anything. So that people don’t get down about their situation. Peter, there’s always someone out there who’s far worse off than you. And I’ve never forgotten that." Alex also recognizes the work he does with the Trust, where he sees people who are having a horrific time when it comes to mental health. He says that he's got friends who deal with depression, and they can’t understand why he hasn’t had depression himself. "I’m very fortunate that I didn’t struggle with it," he says. “Alex Lewis, what a wonderful attitude! I think that's pushing the boundaries in itself. Would you agree?” "Yeah… probably it is." When Alex meets people in the street, he tells me that most of them assume it's a bomb that’s hurt him. Over the last 12 months he’s spent time learning from countless other amputees, many of whom are injured servicemen who he’s met through sessions with the Special Forces charity "Pilgrim Bandits". The experience, he says, has made him acutely aware of problems surrounding amputee care. “The huge issue with amputation is money,” he explains. “It’s just not there. A normal six inch cooking knife for me to attach to my arm is £650, for instance. A thrower for tennis balls, which enables me to walk the dog, is £600. If I can get some full prosthetic legs, which I hope to in the next couple of years, they’ll be £90,000 each – and that’s before you buy an ankle, or a foot. It’s not a package deal, by any means…” “You’ve obviously thought about this,” I say. “It’s not just coming out of the blue.” “Yeah, absolutely. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about it. And you have to try to work through every possible situation. It takes a lot of time, but that is the only way I could get through it.” “Let me ask you this,” I say. “Are you able to get away from it at all, Alex? Is your situation – your current life – all-consuming? I mean, you’ve told me you want to be the best husband, the best father… noble goals for any of us. But are you able to put your situation aside and just focus on being that father or that husband or that friend… or is what happened to you always there?” “No, no, I can definitely put it aside,” he insists. “If I’m mucking about with my little boy, I do put it aside. I think you have to. You just can’t think about it 24/7. If you do, you become engulfed with it. It takes over your life: there’s nothing else. I mean, it’s a fine line. I’m lucky because I do a lot of activities with military guys and I raise funds for the military charity, and we do kayaking, cycling, skydiving. And when I’m with those guys, I feel absolutely normal. Feel like I’ve got an able body. And that helps: being with like-minded people and also giving everything a go. When I realized that all my dreams had gone, I thought I’m either going to worry about it, or not do anything or go out and find what people were doing and let’s give it a go. Let’s try it and see how we get on. And I was lucky that with the charity I got involved with, they got behind me and they helped. And this year I fly to Africa, next year to New Zealand… I get to do some amazing things! And I’m incredibly grateful for that.” Back when he left the hospital, one thing Alex knew was that he didn’t want to just sit around. He was keen to get out into the public so they could see him and see that he was willing to come out. He wasn’t going to hide away. “I tried to encourage people to come up and talk to me,” he explains, “and I’d chat with them whenever I could… I always made myself accessible, really. I didn't want any pity. I wanted to be perceived as a person, not a disabled person, and someone who has gained knowledge from what’s happened. I wanted people to see that I haven't been knocked down, I’m not sad, I’m not defeated. I’m just trying to push myself forward, get back to as near a normal life as possible. I felt that was incredibly important, to get out and see the public. The more I did it, the more recognition I would get. It’s been lovely, really, the interest people have shown.” “So, how are you handling fame?" I ask. "I mean, you’re famous, man! Documentaries, media articles, TV, all sorts of things…” He holds back for a moment, then figures: what the hell: “Honestly, I quite like it,” he laughs with enthusiasm. “I’ve enjoyed my 15 minutes!” I tell Alex about my conversation with Rick Hansen, "The Man in Motion" (Chapter 8). "It occurs to me that you, and Rick, and Nicole Moore... you all share an amazing attitude: you're full of courage, you’re each very positive, you’re very committed to helping other people, you’re committed to encouragement and inspiration. And I truly think that’s wonderful. I really don’t know how you do it. More particularly Alex, if our positions were changed, I don't know that I could do it!” “You know Peter, I find it quite sad sometimes that there aren’t more people who don’t give up their time to help others,” he tells me. “I get quite frustrated sometimes because when it came to the man-hours spent on me, the surgery, the doctors, the healthcare assistants… the number of people who devoted themselves to me… I always felt the least I could do when I came out the other side is to give some of that back. So many people did their level best… and they all went above and beyond. And I will never, ever forget it. Nor can I really thank them.” (Makes me thank my lucky stars that I've always given back to my community through volunteering for charities.) “But what you're doing by creating awareness is a form of thanks, Alex," I say “Yeah, yeah… I mean in the U.K., the Health Service gets criticized like crazy but I don't see it that way. They are amazing and it's important that people know that. If you lived in the U.K., you'd realize how lucky we are to have that service. I mean, a lot of us are here, alive, thanks to them.” “Alex, I want to get back to the theme of pushing the boundaries,” I say. “When I say that phrase, tell me what goes through your mind?” “You know what, I don’t think I have any boundaries anymore,” he says. “I do want to push myself as much as I possibly can, whether it's physically, mentally, whether it’s helping with the bionic prosthetic… it’s kind of taking the shackles off in a way, and having a free run of it. That’s how I view it. I don’t think I shall encounter boundaries from what I’ve gone through: I’ve gone all the way down and come up on the other end. So now I feel very free, really. And I want people to see that. You can change. You can take the risk. That to me is pushing the boundaries!” Alex and I discuss the concept of life’s only limitations being those that you set yourself. “I agree with that,” he says enthusiastically. “100 per cent! For me, nothing is out of reach. And I want my son to see that. I want my little boy to grow up and see that at no point his dad stopped trying. I want him to be so knowledgeable and see that there’s nothing that you can't do." Sam is 6 as we talk, and I tell Alex the boy is lucky to have a dad like him to teach those lessons. “Thanks Peter, but he’s got an amazing mother as well,” Alex reminds me. “Sam’s laughing all the time.” “How about your family? How about your friends, associates who are around you?” I ask. “Do you think they see you as someone who pushes boundaries?” “I hope so,” he tells me. “I do hope so. The old me has just moved on and now I want to do things that most people wouldn’t even dream of doing. That’s just as important, especially for children: they can grow up believing that anything is possible. What a gift.” “Ever have any doubts about what you're doing?” I ask. “You know, just live a quieter life?” “No,” he replies with certainty. “No. You know, with the military guys, we actually dream up these exhibitions and there’s a great world out there I never knew existed. I don't say no to anything that comes my way. And I think that’s really important. And I want to do it all now! It’s the exact opposite of what I was four years ago.” Indeed, this is a guy who’s recently jumped from an aircraft and has gone kayaking to Greenland (210 kilometres in seven days). "Yes, yes,” he says, “especially with no arms and no legs. It's been quite an interesting path to getting used to the kayak, but it's a phenomenal opportunity. Mind you, my goal is to play golf in the Paralympics in 4 years." He pauses, looks off, then adds in a whisper, "Peter, there's one more important goal: I plan to walk down the aisle unassisted when I marry Lucy!” I always find it difficult to say goodbye to someone I’ve come to know and respect so much. But that occasion is here. “Alex, I can’t thank you enough for making time for me. I know how busy you are. But I do want to say you’re an amazing individual. You're fearless. I do think you push the boundaries with incredible zest and amazing resilience. And I’m so glad you do that because I know you’ll leave this world a better place. You’re going to create a big difference. Good on you for doing so!” “Peter, thank you very much, you’re very kind, very kind. It’s been a real pleasure talking with you." My final memory of spending time with Alex Lewis? It’s when he tells me, “Fundamentally, I’m still the same guy. But my path has made me better.” Now there’s a man who’s comfortable in his own skin. * * * Thinking back about my time with Alex, I know he taught me the incredible value of maintaining a positive attitude no matter what dilemma befalls you. Overcoming your own feelings of bleakness and desolation in order to lend a hand to someone else pays huge dividends, every time. Other people I interviewed for this book have given me terrific lessons too on setting aside fears, taking on risks and working beyond any limits that have been set for you or that you've set for yourself. But it's Alex Lewis who's confirmed that you can always change for the better when you have to. And that to me is pushing the boundaries.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|